Warning: This is a long post and Substack is telling me Gmail will direct you to the web version after a certain length. I recommend getting a coffee / beer and reading the web version.

This is my fourth post in Book Corner, where I attempt to find investing lessons in any book I think is investing related. Check out my previous posts on Netflixed, King of Content and Dead Companies Walking.

Everyone reading this at some point has had to do some research to vet a business (could be a vendor, a stock pick, a landscaping company, etc.) and concluded that everything checks out. The few times I’ve gone “there is something wrong here” the signs have been obvious - terrible Yelp or Glassdoor or whatever reviews, Google searches that show a history of controversy, management with questionable backgrounds, etc. Never have I encountered a situation where my research disagreed with the consensus on whether the company was following the laws.

Enter David Einhorn’s Fooling Some People All of the Time. This book is a near decade odyssey of one man’s battle against the consensus. David Einhorn unveiled his short thesis against Allied Capital in 2002 at a charity conference. At the time, Allied was considered a generally buy-rated BDC (Business Development Corporation) with a decent track record of raising the dividend year after year.

Einhorn’s first public speech on Allied correctly (correctly in retrospect - at the time this was hotly debated) accused the company of misleading and illegal accounting. BDCs are required by law due to the Investment Act of 1940 to use fair value accounting, which means marketing assets at a value they would expect to reasonably receive in a sale.

If a market quote is available, the BDC should use that quote. Allied did not use these quotes and the book is chockfull of examples of Allied valuing debt close to par when the market was at cents on the dollar. As you read on though, know that Allied mismarking assets is not even close to the worst part of this company and I’ll spend the second part of this post talking about a large subsidiary’s criminal behavior.

I want to run through some of the many examples Einhorn provides to show you how egregious these mismarkings were.

One clear of example of Allied ignoring the debt market for two debt securities it owned:

Yes, you’re reading that right. Allied is at 100 when the market is at 10 and 4 on Velocita and Startee, respectively (these are real quotes to be clear - these bonds traded at those values at those points in time).

Here’s a good one for Sydran Foods:

Take a second to review that graphic. That’s basically four years of ignoring a disaster.

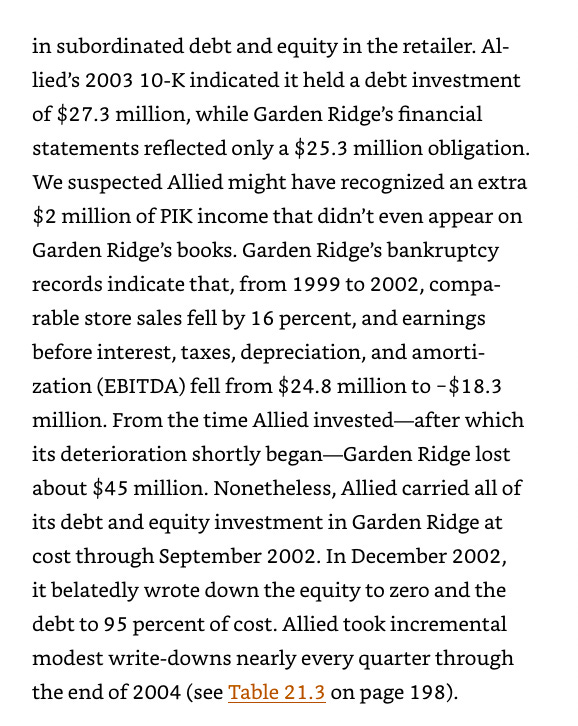

Another wild one for a bankrupt company called Garden Ridge. I’ll let Einhorn tell the story:

Yep, another example of several years late to the party on accounting.

Imagine looking at Allied’s book value during this time and not knowing what Einhorn knew. I’d probably be one of the retail traders going “Look at where this company trades relative to book and the amazing dividend! What a buy!” Clearly, book value can be and has been misstated by public companies.

Allied also owned subsidiaries with publicly traded debt and failed to mark down the equity when the debt plunged (as my buddy is fond of saying, “A dollar to the debt is a dollar from the equity and vice versa”). To add insult to injury here, Allied would routinely issue stock when the company was at valuations that leveraged its mismarked assets, meaning its investors were funding this accounting fraud. Seriously, here’s a picture from the book with all the equity sales the company did:

It’s worth noting here the underwriters received millions of dollars here for distributing these offerings and probably gave Allied favorable coverage in return.

Einhorn’s first speech on Allied led to some increased coverage on the stock, but it took nearly six more years for the company’s valuation to materially change (and really, the financial crisis sped up the process a lot). For those keeping score at home, if you short a stock and it goes to zero six years later, you’ve doubled what you were able to borrow in six years before the interest costs of borrowing the stock. Allied’s stock price is crazy to look at considering Einhorn had the whole fraud figured out quite early:

This all in spite of the fact that Einhorn’s speech caused Allied to change their accounting nearly immediately, as it became obvious the company was out of compliance with a number of SEC rules for BDCs, including how they recognize net investment income:

Again, in retrospect, everything in that speech was spot on, but it took almost six years for anything to happen on the stock. The reason this book is worth reading is to see a real case study in how the most logical arguments in bull-bear debates do not always win. Rather, a confluence of marketing, who holds the equity, government agencies, public sentiment and more get you to where the market trades at.

Allied’s behavior against Einhorn is another big factor that probably helped the stock stay afloat. The company did everything it could to encourage the SEC and press to go after him for “manipulating” the stock. Allied also hired a combative lawyer that helped multiple US presidents escape scandals, pulled phone records of Einhorn and those close to him and gave Wall St. meaningful business on equity offerings and other financial products to get analysts to either drop coverage if they had bad things to say or write positive things about it.

I should add here Einhorn’s work was based on a lot more than just reading financials and reviewing the related assets. For example, early on in his research, Einhorn finds the company’s statement from its auditor changed such that its primary auditor wouldn’t attest to the accuracy of the valuations Allied stated. As is the pattern though out Einhorn’s battle against the company, Allied makes an excuse about a regulation that sounds plausible but under further inspection makes no sense. Einhorn’s work here that really shines that I think few investors would do is going on the ground and getting intel on Business Loan Express, an Allied subsidiary (he even hires Kroll to do a private investigation).

I mentioned earlier the worst part of this fraud wasn’t the financial shenanigans - it was the criminal activity going on at Business Loan Express (BLX), a loan originator and large subsidiary of Allied. Einhorn finds significant instances of this company originating loans that defaulted nearly instantly. BLX had preferred lender status with the Small Business Administration (SBA), meaning the SBA would guarantee a portion of many of the loans.

The borrowers on the other sides of the loans in some cases had criminal records. In other cases the value of the properties used as collateral were significantly inflated so BLX could write bigger checks. The book has pictures of one property that basically is a collection of weathered shacks that BLX gets an appraisal for at $4 million. Einhorn and several others who were investigating Allied provided the government with reams of evidence of fraudulent loans, but for various reasons the evidence goes nowhere until years later.

Allied meanwhile does whatever it can to keep BLX’s valuation afloat. It changes methodologies and uses a set of comparable “peers”, and then swaps names in and out of the peer group. It doesn’t write down BLX when the government announces an investigation into the Detroit office of the company. All the while, Allied stock does fine.

In short, this book is a fascinating read because it shows you how many factors go into the price a buyer and seller are willing to pay. No matter how great your research is on a company (and I’d argue it’s hard to do better than Einhorn does here), the market wakes up to its realizations of the truth on its own timeline. While in retrospect a company may be an obvious fraud or an obvious home run, try living through nearly six years of dead money on a trade.

Einhorn’s vigilance is a testament to his moral compass and he did a whole lot of good in the world by changing how the SBA evaluates lender partners and forcing the SEC and others to review BDC accounting. He also donated the money from the trade to charity. This is a fascinating book from start to finish and shows you among many other things how good things take time.

Alright, some quick closing thoughts:

The financial crisis and Einhorn’s famous short Lehman trade is tucked into the epilogue of this book because Einhorn finished the original before it. I’m not sure how readers of the original version felt about Allied and Einhorn. Some later unsealed evidence against BLX is also presented that shows you how widespread the bad behavior at BLX is. Additionally, Einhorn talks about how Lehman really was the same / similar trade (lender making questionable loans with questionable accounting), but just was on an accelerated timeline because of the financial crisis. It’s funny how opinions are formed about companies post-hoc instead of while frauds or amazing success stories are happening. Annie Duke calls this “resulting”.

Many longs (especially passive longs) haven’t really done their homework. Einhorn tells a story about a mutual fund manager who had a long Allied position. He was interested in finding out why the guy was long, so he had a sit down meeting with him. The manager basically told him he liked the dividend and valuation… and then dropped his position next quarter after Einhorn presented him with the short thesis.

Do I really know the companies in my portfolio? That’s the subtitle of this post. When you read the nearly 400 pages of Einhorn’s analysis, it becomes obvious knowing a company is a lot more than reading SEC filings and transcripts. Talking to management is really just one angle. I have to believe the on-the-ground diligence Einhorn did on BLX really got him over the hump. Not everyone can hire a private investigation firm, but notably another investor did his own research on BLX and got Einhorn some leads, showing that the average Joe is capable of gaining this type of alpha.

“Trading at a discount” is always second to “What are the assets and liabilities that get me to book value?”. I love discounts to book and I actually just listened to a whole podcast pitch on NXDT that is about a 40%+ discount (and many will remember my TURN posts also mention a huge discount as a reason to buy). I made a very good trade a few years ago on CPLG that was based on a discount I thought could close, so my ears always perk up when I hear about stocks trading below book. Importantly, I did not do 10% of the research on NXDT, TURN or CPLG that Einhorn did on Allied. To really pursue trades where the thesis is discount to book, you need to have your own well-researched valuation of company assets. This book was a very humbling reminder that this research takes time and also that…

Consensus bets that trumpet financial metrics (forward P/E, P/B, EBITDA in 2023…) deserve close scrutiny. Allied increased their dividend every year for years and looked attractive to value investors at various points in time (including near the end of the financial crisis when it could be had at a fraction of its stated book value). When I look at FinTwit today, I see a ton of posts that begin a conversation with how cheap a company is. The story of Allied to me shows that perceptions of cheapness come from:

The company’s accounting, which can be misleading

Management’s estimates of the future, which can be misleading

The company’s track record, which can be misleading (dividends paid out of cash or one-time cash gains for example shouldn’t be used as indicators of where the dividend could go)

I’m going to make it a goal for myself to try to vouch first for the accuracy of what management is saying and doing / has done before getting into how cheap a stock is on traditional valuation metrics.

In summary, the best research goes extremely deep and isn’t necessarily capable of convincing the market until years have passed. Fooling Some People All the Time was a reminder how hard investing is. Being right isn’t everything.