We don’t normally think in terms of revenue multiples, but we found real appetite among investors who do…

To determine possible exit values for later stage companies, tech growth investors often focus on two key and interconnected questions: (1) How long could this company grow at high rates; and (2) What will its margin structure be over time? So while two companies might have similar revenue numbers today, their actual expected revenue, cash flow, and ultimate outcomes could be very different, depending on how investors answer these two questions… and therefore, those two companies ought to have different present-day valuations and multiples.

I’ve had a few conversations with people recently on whether the gigantic drawdowns on some once-beloved tech names merit giving these names a further look. When prices drop enormously, the temptation is always to assume the related stocks might be getting cheaper on sellers overreacting… but we all know that’s not always the case. Prices are just marks determined by buyers and sellers and mean nothing in a vacuum.

The mental model I use to think about “fair value” is what I’d pay for the company if I could bid to take it private, which I attribute to Warren Buffett but may have come from elsewhere. As a related aside, I enjoy the game where people give me some relevant metrics and commentary on a company without revealing the name and ask me to guess at the market cap. I can think of no better exercise for thinking more critically about valuation than saying what you’d pay without looking at current and past price. Even better if this thinking exercise doesn’t include exit multiples and is a pure look at “if I had the chance to own this business and wasn’t allowed to ever sell it, how much would I pay today?”

Unfortunately, most conversations I’m having on growth stocks today usually include the following two points:

Hey, this name is in a 40% drawdown and back to pre-COVID levels

This company is going to grow 30%+ for the next few years easy and trades at only 20x sales!

You’ll notice both of these points include a reference to the current price or a reference to some absolute number sales multiple.

Stepping back, I don’t think the fact that SaaS / tech / growth is in a massive drawdown should impact whether you’re interested in these stocks. In a perfect world (and I admit to not doing this), I’d set some price alert based on the current number of shares outstanding (maybe increase to assume modest dilution) and what I think the equity is worth based on a DCF and then buy when my alert goes off. Where the stock has been should be irrelevant if you’re bidding purely based on taking the company private and owning forever.

If I had unlimited cash and had to place a bid to take a company private and own forever, I think I would come up with a number by doing the following:

Start with the idea that I want to get a 10% annual return by the time my non-existent kids are old enough to help run the business (so say 25 years from now). I want my return to only come from cash the business can generate, because remember I can’t sell the business (note - this can include terminal value of cash flows). When the kids take over (“take over” - read on for more), the business should be worth more than 10x+ what I paid for it (1.10^25)

I want my projections to be relatively conservative. This is a loaded term, but I basically mean here I don’t want to assume that Web3 will take over the world or that everyone will work from home in augmented reality. On the flip side, I want to be careful about assuming the world will stay perfectly still (so business should have shots on goal as it pertains to new technologies / ways of doing things / insert your favorite lesson from Clay Christensen)

I don’t plan on running the business re: day to day operations and want the existing management to remain at the company. If possible, I do not want to have to be involved in strategic decisions and want to be able to treat my 10% return as passive income

I know, big asks right? The margin for error is small to notch a 10% return (returns can only come from cash from business, so you can’t sell it to a higher bidder) for 25 years straight and paying a high price means that margin is even smaller.

Sales multiples to me are meaningless in this scenario because they tell me nothing on the cash a business can generate, so I can’t make any calculations to determine if that 10% return from cash is possible. So when it comes to determining if SaaS is cheap, as a16z points out in the earlier quote, I have to know margin structure over time. How much of sales will be left over after all cash expenses and necessary cash investments (capex) are paid (basically, what is FCF margin)? Given a 0% or less free cash flow margin, I will not take the business for free. This point is obvious to everyone, but is the foundation of more statements just like it:

Given Company A and B have the same starting revenue and growth rate, if A has ending 20% FCF margins and B has 10%, I’ll pay 2x as much on sales multiple for A versus B.

Given Company A and B have the same starting revenue and growth rate, if B requires twice as much capital to grow as A, I’d pay even more than 2x the sales multiple more for A than B as A can grow just as fast as B at half the capital usage. The leftover half can be used for whatever A wants (call it a free call option)

Not only that, if both companies have to raise capital through equity or debt to keep growing, A likely has a cheaper cost of capital than B

What I’m getting at here is the only real way in this hypothetical to tell how much you would pay for a business is to look at cash over time. My posts on VMEO and NET both tried to make this point - I considered each one expensive when I wrote about them because the current price implied massive cash generation, more than I thought either was capable of.

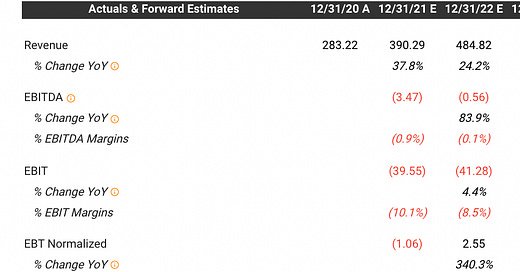

Is VMEO expensive now, after a 75% drawdown? Estimates in TIKR show me the following for 2022:

So using these numbers ($484mm sales, 9% starting FCF margin) and some numbers of my own:

25% growth for next few years (consistent with investor day presentation)

5% growth after that

22% FCF margin after that (pure guess)

I can get to a 10% return after 25 years with only cash coming from the business (I assume FCF all eventually comes back to me):

This is all well and good, but the big problem I see here is that most of the cash return comes from the later years. It remains to be seen whether VMEO can become a big company and raise FCF margins. I thought it was interesting here to look at returns at any point in time:

I don’t even reach a positive IRR until year 12 here. I think this is one of a few reasons why SaaS multiples could continue pulling back - most of the names involved don’t support a positive cash return until a decade or more in the future with major growth and margin assumptions.

You might be reading this and going “well, what about the 10x P/FCF stocks you pitch? Aren’t these 10 years basically to get your money back?” The answer here is yes, but the difference is in Year 1 I’m starting with a 10% FCF margin, not assuming any growth or margin expansion and getting my cash back in 10 years. In my “take a business private example”, I might feel more comfortable making no growth assumptions than growth + margin improvement assumptions.

The title of this post is “Is SaaS cheap yet?” SaaS is already cheap if you believe in continued growth and margin improvements for certain names. It is expensive if you don’t buy these forecasts. Here is my draconian VMEO forecast, which gets you a measly 4% IRR:

I took back early growth to 15% and lowered margins to 15%. If you assume this forecast is right, you need to pay about $1.25bn for VMEO to get your 10% return - that is about a 50% drawdown from today’s prices and 2.6x forward sales. Recall VMEO already has drawn down 75%.

Growth stocks could get a lot worse before they get better. It all depends on your growth and margin forecasts.